“His music is current. It contains a sense of tradition with an edge. It is not boxed in, and it has a current writing style.” —Nové Deypalan, D.M.A.

Andrea Morricone’s illustrating his points

John Middleton Murry once said, “For a good man to realize that it is better to be whole than to be good is to enter on a strait and narrow path compared to which his previous rectitude was a flowery license,” as Parker J. Palmer quotes him, in “Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation” and amplifies in “The God whom I know dwells quietly in the root system of the very nature of things. This is the God who, when asked by Moses for a name, responded, “I Am who I Am.”

It is with a sense of certainty that Andrea Morricone describes who he is as “perhaps already swimming in music, conceived in the womb of his mother, Maria, listening to the music of Ennio, his father, a trumpeter.”

I feel blessed that Andrea Morricone — a world-class composer of “L’Inno All Fede” (Hymn of Faith), a Vatican acquisition, “Anthem for Russia” performed for the Russian elite, in “The Musical Seasons at the Constantine Palace at St. Petersburg, Russia, in 2014, and “La Forza del Sorriso,” a theme song to be sung by Andrea Bocelli at the Expo Milano 2015 — would reach out to Filipino-American talents.

I was generously brought into Maestro Andrea Morricone’s life orbit by his colleague and effervescently cheerful assistant, Salpy Kerkonian, and tenor par excellence Christopher “Pete” Avendaño. I then invited Dr. Nové Deypalan, who graciously attended the dress rehearsal of Andrea’s Christmas Concert 2014 and gave me a mentoring session on Andrea’s composition notes which I took during the interview.

Andrea Morricone created original compositions, including new arrangements for these hand-picked Filipino American artists: “Canzona Filipina,” “Ave Maria,” ” YOU” for Pete (tenor), and a choral accompaniment from the a cappella winning champions and silver medallists Children’s Choir of Immaculate Heart of Mary School and their companion Holy Family School (chorus) and “Adagio in C Major” for Cello, Harp and Strings for Matthew John Ignacio (solo cellist) and a graduate of Colburn School of Music.

On Dec. 9, 2014, Andrea Morricone shared his timeless theory of musical composition, which is perhaps an exquisite synthesis of an entire history from traditionalists composing classical music, to the romanticists, to the Germans, to today’s composers.

He walked into the offices of the Asian Journal, en punto, and greeted us: “I am honored to be in your presence.” It was such a reversal like an avowed world-class artist and an Oscar award-winning film scorer when one is greeted, not with the aplomb of snobbiness, but with humility and gracious warmth. It was unexpectedly disarming.

For this writer’s sense of bearing and certitude, Ding Carreon, the Asian Journal’s photographer/videographer, videotaped this historical gift of encounter.

“What does it feel like to compose music for God’s representatives in the Vatican, Russia, and a world-class artist, Andrea Bocelli,” I asked the maestro. “That would be for the musicians who play my music to answer,” he humbly responded. Instead, he articulated his wish to do a concert in Manila and conduct an orchestra of highly skilled musicians.

“I am very happy and thrilled about the music itself! What happens to me is this big work, music that comes from far away, in the sense of time, in the sense of information, [the] result of a long process, [of composing, of creating,] even if it takes only two to five minutes a piece. It is a piece that is meant to be.”

The elements of his musical composition: concepts of necessity and madrigalism

Much like the “Canzona Filipina,” which Andrea composed in only an evening (the night before the Christmas Concert of 2014, in fact) based on Felipe de Leon’s work of creation, “Payapang Daigdig,” which was inspired by waking up to the morning after the destruction of Manila during World War II. He arranged Felipe de Leon’s piece from a “deceptively simple, yet complex and created by a person who is well versed in music” into a piece of virtuosity that defies description of words, other than to witness the Amor Symphonic Orchestra members (mostly LA Philharmonic musicians) give life to Andrea’s beautiful arrangements, that made the packed St. Mark’s Church clamor for another encore, to which the maestro obliged, with “The Theme in D minor.”

Imagine Andrea’s self-restraint in considering his impact and opting instead to talk about three elements of classical music composition: the concept of necessity, the concept of madrigalism, and the shape of a melody which shows up as a question mark, unanswered. It is like any piece of art, with enough ambiguity, vagueness, or even metaphors to allow the reader or the viewer’s interpretation to come forth.

But the concept of necessity, as described by Dr. Nové, is similar to when cooking with too many spices, one loses the dish’s essence. Much like music, each note has to serve its purpose, “if it is necessary, put it there.”

Andrea describes that in his music, it is important that there is order. That ultimately, the musical composition has to have a good sound. But it also has aesthetics, an order, organized art verse, a refrain, a chorus or a climax, a sense of arrival, a descent, and an ascent to the summit, before the descent.

I interviewed a young composer who shared her original compositions from her dreams, on-demand, or inspirations.

This piqued the maestro, who quickly said: “I do not believe in dreams, I prefer to sleep. But music comes to me all the time. In music, I choose.”

It was as if he was describing all of his inner molecules are made up of music, his heart, his mind, his soul, and his entire spirit breathed in and exhaled music.

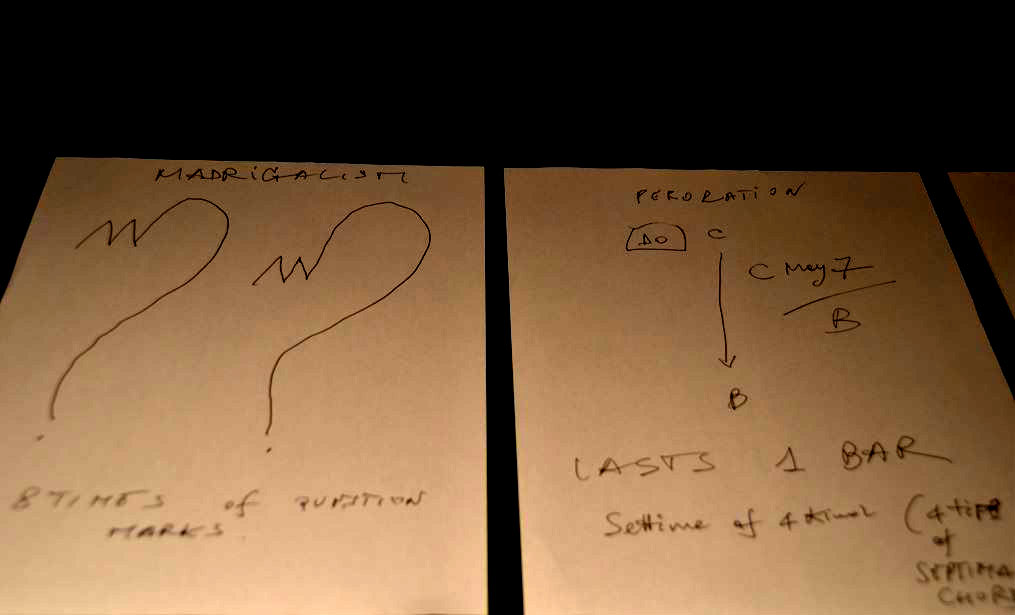

He drew a half a heart symbol, with rugged tips at the base of the heart and a smooth apex, and wrote, “eight times of question marks” and its title, “Madrigalism.”

He illustrates more by writing peroration, where most composers create at C Major 7/ over B, and that tune would last a bar, forming four tips of a Septima chord.

Dr. Nové explained that during the 19th century (Liszt), there was an interplay of music and landscape. Musicians told a story through their music or described it as their music shared their life stories, there is a strong madrigalism.

“The shape of the melody shows up as a question mark” in Andrea’s compositions. Perhaps, this is the signature Morricone sound that Enrique de la Cruz, Ph.D. (this writer’s husband), describes after listening to Andrea Morricone’s Christmas Concert in 2014.

Andrea continued, “It is a big question mark that everyone has to deal with by himself. The melody appears four times, it is the same question mark, and eight times question marks become infinity. The oboe starts high (when the maestro at rehearsal calls it a crescendo), and then it curves down, where the oboe is now reacting to the question mark. There is no piece in the known history of music making by men, according to me [referring to himself, Andrea], there is no chord C Major F, over B lasting over a bar. It is difficult to find a Septima of four or four types of Septima chords.”

“The tension it creates keeps going up and up, it is huge, and the oboe keeps going up, I believe, something unique.”

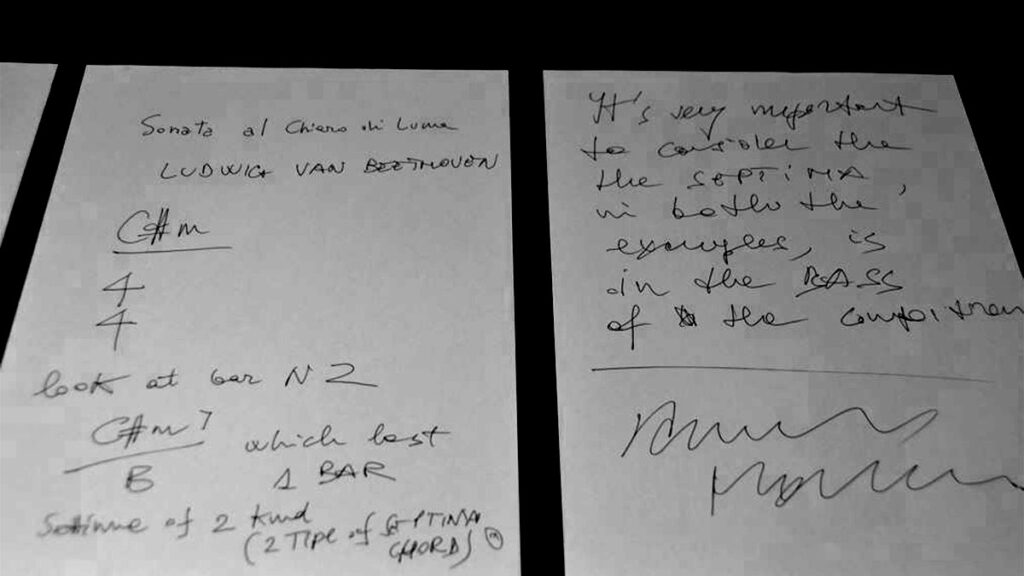

The closest composer coming to what Andrea has done is Ludwig Beethoven, in his “Sonata Al Chiero de Luna,” according to the maestro. I validated Andrea’s statement by interviewing Dr. Nové Deypalan, another music conductor and arranger who has a D.M.A. (Doctorate in Music Arts) from USC, and he, too, affirmed that the maestro’s statements are historically true and accurate.

During the medieval period, circa 1150 to 1400, Gregorian chants were created. For 300 years, the rules were about one music line, monodic. Recall hearing Lamentations by Thomas Tallis or works of Giovanni Pierlugi da Palestrina’s Adoramus te –in early Latin masses that we were steeped in as Catholic Christians?

I might be losing you by now, my dear readers, but stay with me as it gets better.

After being constrained for 300 years, i.e., creating music using one music line, Renaissance artists started their own ways of composing music, flexing their creative muscles of freedom.

From 1400 to 1600, Renaissance musical composers created movements called “harmony” and “polyphony, “ organizing them into major and minor music scales.

Recall Leonardo da Vinci, who did an exquisite synthesis of face and landscape with a timeless classic painting of Mona Lisa, which to this day, attracts an admiring pilgrimage of travelers? That was the period of 1503 to 1506, as the freedom in music grew, so too were the paintings, art, and architecture.

The likes of Johann Sebastian Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi also paved the way for their Renaissance compositions to be played by a modern orchestra.

During the Baroque period, circa 1600 to 1750, these artists gave birth to more musical genres: chorus, sonata, opera, cantata, and even bolder strings of a violin, viola, cello, and harp. Color and textures were used to describe their distinct sounds.

The classical period of 1750 to 1830 gave the world the likes of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn, followed by the Early Romantics composers of 1830 to 1860: Verdi, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Chopin, and Berlioz.

“If Baroque music is notable for its textural intricacy, then the Classical period is characterized by a near-obsession with structural clarity, “ according to Naxos, while the late Romantics made music “often pacing their compositions more in terms of their emotional content and dramatic continuity rather than organic structural growth, “the likes of Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Puccini, Strauss, while the post-war periods gave us diversity, experimentation of styles, the likes of Gershwin, “THE RHAPSODY IN BLUE,” and of course the diabolical sounds of Stravinksy.

Mahler#8, if you recall, was conducted by the exuberant musical genius Gustavo Dudamel, with 1,000 musicians in the Shrine Auditorium. This writer wrote of the participation of the Philippine Chamber Singers-LA in that vast, historic collaboration.

Exquisite synthesis of traditionalist and modernist composers.

Now fast forward to the 21st century, and here comes Andrea, who captivates us with his work, now eloquently described as influenced by traditionalists, with a signature sound of his father Ennio Morricone, yet, distinctively Andrea’s, with his own creative edge, and educated by the music of the early classical musical composers.

Andrea likened his music to approximating Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Sonata al Chiaro di Luna” in C sharp minor, and he said, “look at his bar #2,” and Andrea writes in his own handwriting, “C sharp minor over B which lasts one bar, a Septima of two kinds.“

“This is incredible, also an unknown in the history of classical music,“ and “even more unique than what I did,“ Dr. Nové Deypalan admitted to this writer.

“There is a stronger emotional point of view when this is done,” Andrea continued, with a high sense of assurance as to who he is in the context of the timeline of composers. There is not a single person I have interviewed who has this sense of certainty about who they are in the context of history, the now, and the future.

Andrea underscored his theory: “It is very important to consider the Septima, in both of these examples, it is in the bass of the composition.”

He signed his four pages of explanations in his own handwriting with descending ripples of half a heart.

Pete Avendaño described Andrea Morricone’s timeless theory of classical music composition, “Who knows if 100 years from now, his theory might be the preferred art form for other composers to use? It is a clever use of dissonance to highlight and emphasize the harmonic blending.”

Frances Marie Noble-Ignacio described Andrea’s music as: “Dazzling talent, penetrating brilliance, and relentless innovation is the hallmarks of Andrea’s music and musical history. And, it is no surprise that his works, like those of his father, from classical compositions to scores for film and television, have been duly recognized worldwide by some of the most prestigious music industry organizations. Andrea’s unwavering, enterprising commitment to composing and conducting and his repertoire of compositions that pulsate with ingenuity are inspiring, and yes, award-winning.”

If I kept you hanging in this piece, remember the genius mind is like that of an ocean; we cannot contain the ocean waters into a hole in the sand.

Much like our interview with Andrea Morricone, who left us with priceless pearls of wisdom, you are simply left with “Morricone sound,” “Beautiful,” “Exquisite,” “Very Expressive,” “You cannot touch, nor see, but you feel it, the only art form, triggering one’s emotions, one’s tears, one’s knees to drop in prayer to God, to thank the gifted maestro, who is so generous in giving his creations away, gifts coming from his heart.”

“After 15 years of starting again on my own in America, much like Arnold Schoenberg did in relocating from Europe to Los Angeles, I am now a well-prepared conductor/composer, that from a spiritual point of view, I can tell you that music is all my life and those who are around me belong to me in a very deep way. That man, Goffredo Petrassi, [the grand old man of Italian music, a leading Italian modernist composer] was fascinated by my mind. He felt what I could become in music. Music is all of my life, people who are around me deeply belong to my life. I can say this about Salpy, she plays my music so well, she becomes part of my life, my heart, she is inside here, “ and gestures to his heart as he repeats, “she is inside here.” For me, music is easy. It comes to me all the time.”

As if to underscore he is accessing the collective mind, the intelligence of the collective subconscious, he said, “ What I am living now will be bringing me to another now. I will be in another now, always in the now. My soul is moving into the now. We are made of nows.”

I responded, “the collective nows, our collective intelligence.” Yes, he responded, “I am always now.”

“Your soul is moving into eternity,“ and he nodded his head to my reaction and said, “My life is a big perspective, I can see many images like they all have spaces in my heart. Like all those I have loved before, I still love them.”