Dr. Carmencita Abarquez Agcaoili and husband Arnold during a medical mission in January 2018 in Santa Barbara, Iloilo. | Photo by Prosy Abarquez-Delacruz

My wife is a woman of grace, a woman of character, a woman of strength. She is very generous in spirit and her capacity to tolerate, to accommodate, to forgive anybody knows no bounds.

Arnaldo Agcaoili, husband of Dr. Carmencita Abarquez Agcaoili, in 2015’s Physician of the Year video tribute at Washington Hospital in Fremont, California.

As the title reflects, fundamental laws are meant to guide us to be on the right path at all times, and as law-abiding citizens, to function daily with ethics and integrity.

Beyond these traits really, there are fundamental laws, a sort of a North Star, which animates one’s life to be a place of serenity, peace and joy.

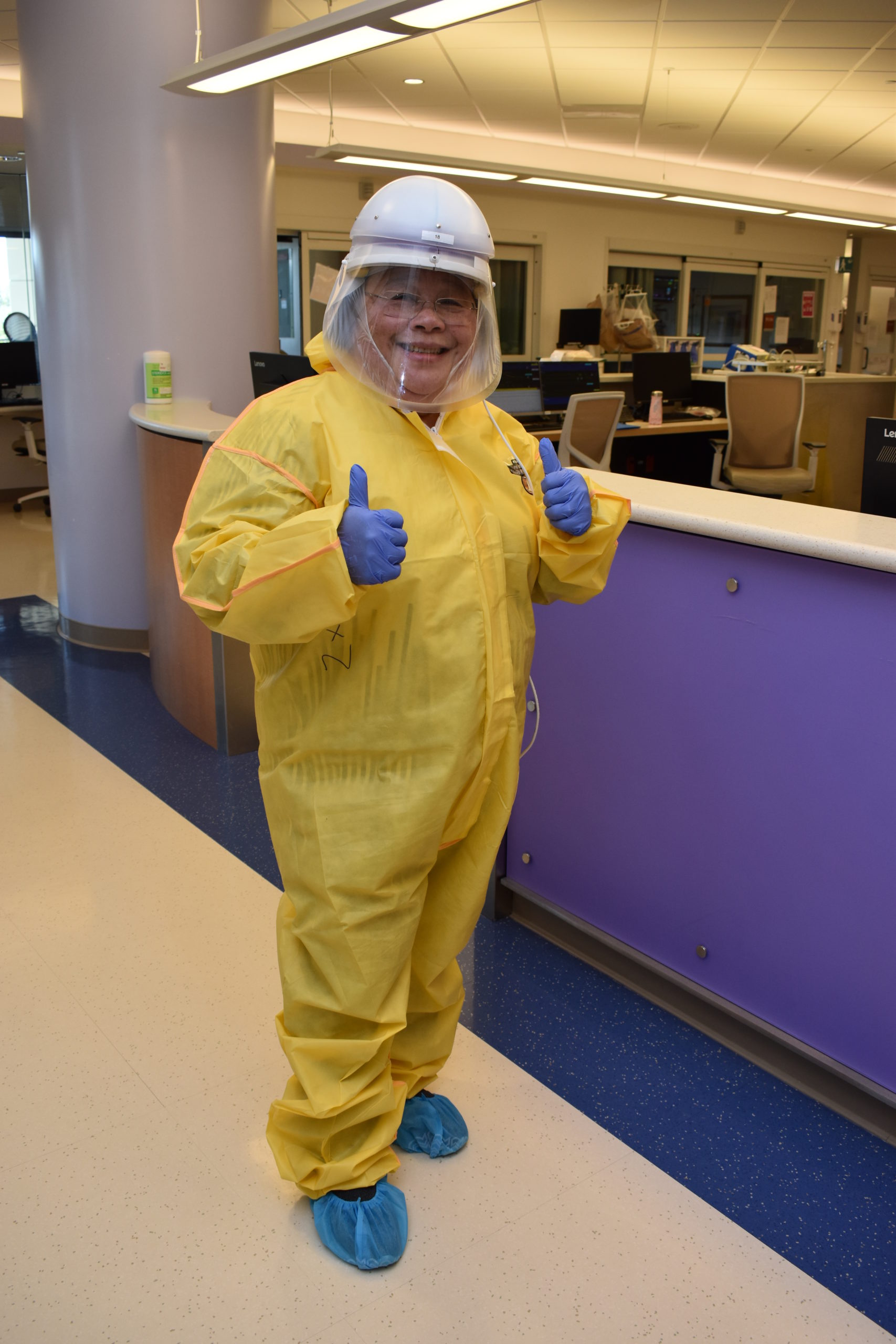

Once you meet Dr. Carmencita Abarquez Agcaoili, a Philippine Medical Society of Northern California (PMSNC) officer/active member and medical director of the intensivist program at Washington Hospital in Fremont, California, you will get a sense of her persona.

At a meeting, Cynthia Bonta, president of the Alameda Sister City Association, asked me: “Have you met Dr. Carmencita,” and added, “She is well-liked by all.” Should I care to know this amiable woman? Is it even possible to be liked and stand out amongst the 150+ volunteers?

During a trip to Santa Barbara, Iloilo in 2018, we were introduced formally. Her nametag had a middle name Abarquez, as my maiden’s surname. Boldly, I approached her: “there are not too many Abarquez names in the world, could you perhaps be my relative?”

“Yes, we are cousins, we frequently visited your home.”

Duh, how could I have forgotten? It turns out her father, Dr. Buenaventura, “Uncle Bonnie” to me, and my dad, Eleazar, were best friends. Both have the surname, Abarquez. Unmistakably, we are related by blood and are connected by good memories in our hearts.

When her family came to visit, our lunch became many afternoons of sharing stories, laughter, and during graduations, a nine-course laureate dinner in Chinatown awaited us to celebrate and after, and a lecture on the value of higher education. There were many more moments like this that I recall and in addition to the stories, the feeling of hearts full.

As I write this piece, I couldn’t help my tears, not an ugly cry, perhaps missing both my dad and my uncle, nostalgic even, wishing those moments repeat.

Just as my mood changed, pulling myself out of regrets, I felt a sense of gratitude to be reunited with my cousin and her family, and with that feeling, I glanced at an apple green butterfly in my backyard, one that grabbed my attention, preparing me perhaps for reflections.

What will my story tell? What would it say about my whole life?

In the successful musical “Hamilton,” created by Lin-Manuel Miranda, these questions alluded to in a song, moved me: “What legacy did I build? What will my story tell? What would it say about me? Whom have I helped? Whom have I guided? What small interactions did I make to others? What would it say about my whole life?”

Would you still raise them when these have been the questions that guided your upbringing?

I surmise these soul-searching legacy questions informed the upbringing of Dr. Carmencita, who credits her dad, Dr. Buenaventura, a physician, surgeon, hospital founder, music aficionado and the father of five other siblings, along with her mom, Conchita, a pharmacist, and the Isabelans she grew up with, as those influencing her philosophy.

Dr. Carmencita was mentored on ethics, life skills, and surgical skills by her dad.

“I shadowed him in major and minor surgeries. From him, I learned hard work, discipline, and inquisitiveness,” she said. “He inculcated in me, ‘Take care of your patients well and you will never go wrong.’”

As Conchita, her mom took care of their family, kept their home, raised six children, assigned them chores and later, in the U.S., took good care of her grandchildren, she also tended to their pharmacy, and the community.

“They loved to host impromptu get-togethers, dancing mostly as well as singing. I was in charge of making the flower arrangements and at times, I [would] pick from the neighbor’s. It was commonly understood that what we have, we share with the community. My dad and mom taught us to have fun, to dance, to harvest the flower blooms, and to decorate the tables for the folks who came to join us for these get-togethers,” she recalled.

The century-old traditional Filipino value of “loving your neighbor” anchored the beginnings of Our Lady of Peñafrancia Clinic and Hospital, a 25-bed facility founded by her father in Santiago, Isabella.

Its mission was prominently displayed on a wood décor wall in the hospital: “With the Blessed Mother, Our Lady of Peñafrancia as a model of love and humility, our hospital is committed to its task of creating a Catholic environment enculturating the values of environmental awareness and responsiveness to the needs of patients and providing optimum care towards the development of a whole person.”

Her dad was a pioneering environmental activist, a visionary in total quality care, and believed in providing medical care for all, including the rebels.

Politics did not determine who got health care. A lot of the folks could not pay, yet it did not stop her dad from providing medical services to his community.

Folks exchanged their labor to help out the family: washing clothes for a week, supplying them with chickens and eggs, and rarely, land titles in exchange for health care services.

Dr. Carmencita met her husband in college while pursuing her bachelor’s of science degree in public health. She completed her medical degree at UE Ramon Magsaysay Medical Center and got married to Arnaldo and from that marriage, they have three children, all boys: Alastair, Andrew, and Alexander.

She first became a research assistant in Neuroscience Institute in UE RMM and after a year, she relocated back to Santiago and became a rural health physician for its Municipal Health Center.

Dr. Carmencita had planned to practice medicine in the Philippines and enlarge the 25-bed hospital in Isabela, founded by her father. This hospital took care of everyone, that her father kept inculcating in her, “Don’t forget to help, and don’t forget to care for them.”

She then became its house staff physician for a year, followed by a postgraduate internship at UP’s Philippine General Hospital for another year.

After Dr. Carmencita gave birth to the couple’s first son, Alastair, her dream with her father was preempted by her husband, Arnold’s dream of pursuing a computer career in the United States.

Alastair, then 2 years old, was left in the care of his Grandma Conchita.

After a year of passing exams, Dr. Carmencita applied for matching residency. She had her eyes set on internal medicine, and while waiting, she volunteered to work at SFGH.

She was a graduate research fellow at the Cellular Immunology and Trauma Center, where she assisted in collecting blood samples for a research study on battered women.

At the end of this research study and with the help of a good recommendation letter from the chief, she applied at 100 hospitals, which resulted in 10 interview requests and finally, two offers for residency.

She accepted the three-year internal medicine residency at St. Barnabas Hospital in Bronx, New York, an affiliate of Cornell University.

Arnold worked in New Jersey as a software engineer, while Alastair was cared for at home, by Grandma Conchita, who has now immigrated to join the couple.

She then obtained a three-year fellowship in pulmonary/critical care medicine at USC-LA County Hospital through her New York-based physician contact, which recommended her. During that fellowship, she also worked as an urgent care physician at Claude Hudson Comprehensive Clinic and a clinic physician specialist at a Tuberculosis Clinic in Northeast Health Center in Los Angeles.

Her family then moved to Fremont, where she practiced internal medicine/pulmonary/critical care with Washington Internal Medical Group for 16 years.

Board-certified in all three specialties — internal medicine, pulmonary medicine and critical care — she also began her long association with Washington Hospital, as a consultant, medical director in respiratory care services, co-director of Intensive Care, co-director of Palliative Care, Medical Director of Intermediate Care and Medical Director of Critical Care Units, a consistent tenure now of 28 years. She is also the medical director of Respiratory Care Services at Ohlone College since 2010 up to the present.

These parent-derived homegrown values of universal care, compassion, and generosity in spirit found convergence in Dr. Carmencita’s choice of working at the mission-oriented Washington Hospital, Fremont. Another factor was to be near her in-laws who lived in San Francisco.

“This is my community, and it is important to me to be actively involved in providing the best possible care for people in our community,” she said. “I get a real sense of fulfillment in caring for patients who are fragile and are at a crucial point in their lives,” the hospital’s website captured her life-giving philosophy in practicing medicine.

She was the team leader in 2017 on an 18-month collaboration of 67 hospitals nationwide, garnering Washington Hospital the Top Performance Award in the west coast from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) ICU Liberation ABCDEF Collaborative.

Health care as a right, not commodity

Isabela was a center of agriculture, growing mung beans, tobacco, and coffee while she was growing up. Similarly, Fremont, located southeast of San Francisco, was an agricultural site for grapes, nursery plants, and olives, following the founding of Mission San Jose in 1795 and the subsequent Gold Rush in the 1800s.

In 1948, compelled by community needs, a group of public-minded citizens founded Washington Hospital. It opened its doors in 1958 with this mission of health care as an “intensely personal service” and a “patient first ethic.”

In 2008, when Dr. Carmencita was working as an internist/pulmonologist/intensivist in a group private practice, she was recruited by Washington Hospital to head and to develop the pioneering intensivist program, attracting trained and high caliber physicians from UCSF, Stanford, and NIH. Starting with 28 beds, they have now expanded to 48.

As the medical director of the critical care units at Washington Hospital, Dr. Carmencita embodies these homegrown values of ‘patient first,’ generosity of spirit and compassion.

“The objective is to provide the right care at exactly the right moment in time to achieve the best possible patient outcome, where the intensivist-led model for critical care has become the ‘gold standard.’ It is focused on patient safety. It improves patient outcomes. It reflects the patient-first ethic of Washington Hospital. It’s the right thing to do for our patients. Patients in the ICU generally have life-threatening illnesses or conditions such as cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, strokes, severe trauma or resistant infections,” she noted. The hopsital’s website explains that “studies have shown that having an intensivist act as the team leader in providing critical care definitely improves the quality of care for these patients.”

In Washington Hospital’s annual report for 2017-2018, their mortalities in critical care of patients went down, an unusual trend considering that sepsis (blood poisoning) is typically a deadly condition that one hardly survives from.

In a month, the hospital would receive 50 patient cases of severe septic shocks and 85% of whom were 65 years and above. If septic shock cases had 40% mortality in 2008, by 2019, it was reduced to 20%, meaning 10 more lives were spared, as opposed to 20 dead patients. The fact that this hospital can treat serious septic shock cases says a lot about this hospital’s level of patient care.

In 2015, the hospital Hospital recognized Dr. Carmencita as its first woman Physician of the Year. A YouTube video tribute captured how her colleagues felt about her, including being “a consummate intensivist” and “a great authority to go to” who “has raised [the] standards of care for thousands of patients. From a fellow intensivist, Daniel Sweeney, M.D, a graduate of the National Institute of Health, “she is a mentor, a humane person, a friend.”

A woman of substance, grace and good character

Last Nov. 2018, the hospital inaugurated a 224,800-square foot medical facility, named after Morris Hyman, who was a community leader, advocate, philanthropist, and Fremont Bank founder. His life-size statue greets visitors and patients in the lobby, as well as a recognition wall bearing the names of the donors who made this Pavilion possible.

In that recognition wall, one notices various donor categories and in the Ambassador category, the top line has Arnaldo Agcaoili and Carmencita Abarquez Agcaoili, M.D. inscribed, a couple who made a sizeable donation to fund the C-pod of the Critical Care Pavilion.

Are you now getting a sense of how Dr. Carmencita has merged her life’s mission of career growth, with giving back to others, in the form of donations, for more lives to be saved in this hospital, along with raising her family?

Would you conclude as Arnaldo, who describes from the quotes above, the essence of Dr. Carmencita’s character and her radiant soul so to speak, a radiance unaffected by folks surrounding her: rich, middle or poor folks?

Spontaneous care anchors desire to make a difference

That “other-self orientation” is what attracted me to Philippine Medical Society for Northern California (PMSNC), the altruism of its nearly 200 volunteers, and the organizational mission of training others and passing on knowledge and skills, while providing thousands urgent health care for a week, each of the 33 years and more, that they have been in existence.

In 2015, when Dr. Carmencita was president of PMSNC, she brought five multi-disciplinary doctors, 10 nurses and other medical staffers in Bohol. Eight staffers of Washington Hospital joined her at the organization’s medical mission in Candon, Ilocos Sur in Jan. 2019. Some are not Filipinos; yet, they cared enough to go to The Philippines on their own dime to help out in surgeries and outpatient care for a week. What moved them?

Try to have a one-on-one conversation with Dr. Carmencita, as joy is her animating force. With broad smiles, she relates how their medical missions went. She shares a slideshow created by her husband, Arnaldo, from the photos taken of thousands of patients helped, plus how the biomedical engineers who go to this mission have given new life to stored medical equipment donated to this medical mission by Washington Hospital.

She rarely talks about what she did, instead, what her colleagues have done to save a life. So her colleagues did the same, talk about how she saved lives as well, miracles manifested so to speak.

She started with PMSNC in 2006 when she went to a meeting for doctors sponsored by a pharmaceutical drug company.

She met Dr. Linda Ursua who recruited her and enthusiastically talked about their camaraderie, their medical mission of helping thousands and the continuing medical education seminars. For a licensed professional, sustained learning of state of the art practices and updated body of knowledge is required. It was not until 2012 when she joined the medical mission, as she was raising her young children. She joined as part of the outpatient team and consulted as part of the pulmonology team.

The first year she joined the medical mission in 2012, Dr. Carmencita encountered a two-year-old child who underwent a complicated cleft lip surgery. While being aspirated, the child became unresponsive, she had to be intubated but given there was no ventilator in this province, she had to do “ambu-bagging,” manually squeezing in oxygen into the airway that goes to the lungs.

The child had to be flown to a larger capacity hospital or she would die not from surgery, but from complications. A 1940s, single-engine plane would fly them to Manila and the usual rental of Php 75,000 ($1,500) was reduced to Php 40,000 ($800), given the emergency of saving a child’s life. The team had no time to wait for a more suitable plane. Arnold, her husband, said, “Let’s go,” thinking it was a Lear jet.

When she got to the airport, she was perturbed that it was a single-engine propeller plane that could only take five passengers, but there were seven of them. So six went: Dr. Carmencita, the pilot, mother and child, an intern and Arnold. Grandma was left behind.

“The pilot started the engine, but it would not start. So, luggages were removed. The pilot came back with a working battery, replaced it and hurriedly flew as a storm was coming. I told the pilot not to go so high as oxygen was getting low at 85% and it should be 90%. The mother of the child started throwing up, as the ride was so bumpy that every time they hit a headwind, it would move sideways. Arnold had to hold the IV for me, and the child’s temperature went up, and the danger was another seizure. The pilot was tapping the instrument panel. The pilot said we lost power and no instruments were working. Arnold started praying. We don’t know how high we were, as we had no contact with the tower,” Dr. Carmencita said in methodically sharing the incident.

The pilot did not tell the passengers that he followed the coastline and did not really tell them the full extent of what was going on. Until they saw, Taal Volcano and asked, “Is that Taal?”

The pilot said yes, all felt relieved that they were near Manila and were given priority to land. “It turns out the alternator was dead, even though we had a new battery in the plane,” Dr. Carmencita continued, “I was pumping oxygen for two hours, alternating with the intern and when we got to Philippine General Hospital, no room was ready, and the emergency room would not be available until one to hours later and all the ventilators were being used. We waited another hour until the grandfather came to relieve us, as there is a cultural expectation that “doctors and nurses are not expected to “ambu-bag.”

After two months of hospitalization, which PMSNC paid for, the boy was able to go home,” Dr. Carmencita recalled.

Not even this scary incident, with a fiery plane crash that could have resulted in losing her own life could deter her from joining the annual medical mission.

Dr. Carmencita and Arnold have gone to yearly medical missions ever since and many more miracles have been witnessed, combining their professional judgment, creative resourcefulness along with resilience, patience to make-do with third-world conditions and still save lives.

What generates her sustained giving is her love of the country where she was born and her love for the Filipino people. In a way, a sense of guilt too, as she promised her father to enlarge the 25-bed hospital in Santiago, Isabela but was preempted when they went to the U.S.

Now, they have their own charity in which they sponsor students in high school to continue on to college. They provide tuition, allowances, and transportation. So far, they have helped a poor deserving student become a lawyer, another a policeman, a teacher, an economics graduate and another with a degree in business.

They are also very active members of their town’s organization, United Vintarinians, which has also helped more than 20 students graduate with a college degree and are now gainfully employed. The organization also supports Filipino veterans with a feeding program in San Francisco every Thanksgiving Day celebration.

Has she made a difference in the world? Does she feel right about herself? Has she fulfilled her dad’s dream for her? Was her husband right in describing her as a woman of substance, grace, and good character? What about her children – what do they say about their mom?

Her oldest Alastair recognized the struggles and triumphs of his mother as a woman of color and an immigrant who dreamed of practicing medicine in the U.S.

“She found a profession that was at first unwelcoming to people like her. But rather than turning back, she persevered, she committed, and she thrived,” he said. “Now, at the top of her game, she is respected and loved by her patients, coworkers, and staff, not the least because she gives back to the community that supported her with projects like the Medical Mission. She is an excellent doctor, a loving parent and grandparent, and a kind soul. I am proud and humbled to be her son.”

While Andrew shared a life’s lesson: “Mom passionately serves her calling. She’s always been my example for hard work and self-sacrifice. Mom always told me: ‘Excellence is one step above average and you can always outwork others’ intelligence.’”

While the youngest, Alexander, has validated Dr. Carmencita’s great example, “Mom has always been an amazing source of strength for our entire family. Her work both in the hospital and at home provides a strong foundation for all of us.”

I say that she has made a difference in the world — her life speaks volumes about love and a legacy of service, I say that now with even more certitude that in her giving service, she has also amplified her self-esteem, even her caring sense of self as an international lifesaver, as an instrument of God’s miracles through PMSNC, as one who directs critical life-saving Units at Washington Hospital, and one who makes a difference in the lives of others, one scholar and one patient at a time!

Would you agree that she follows her own North Star – the fundamental laws of her giving self: compassion and generosity of spirit to others?

Published on Asian Journal