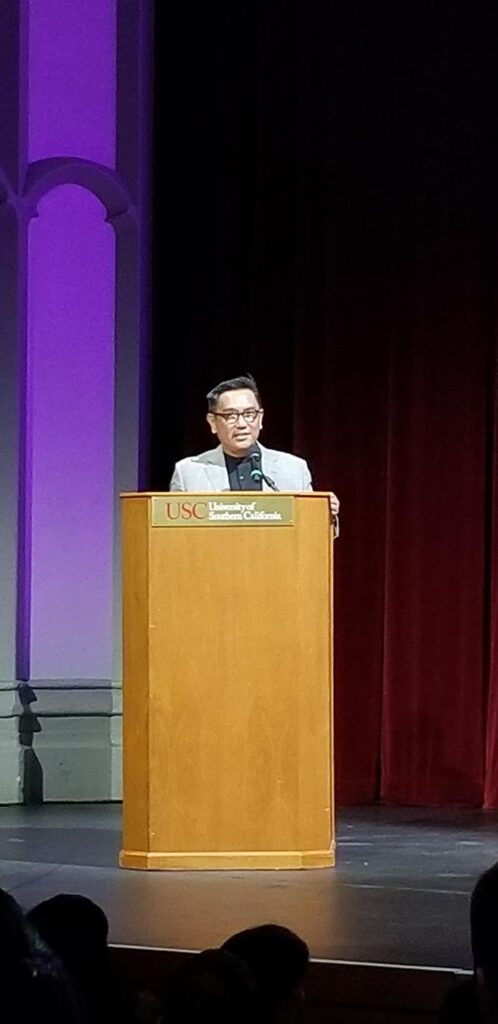

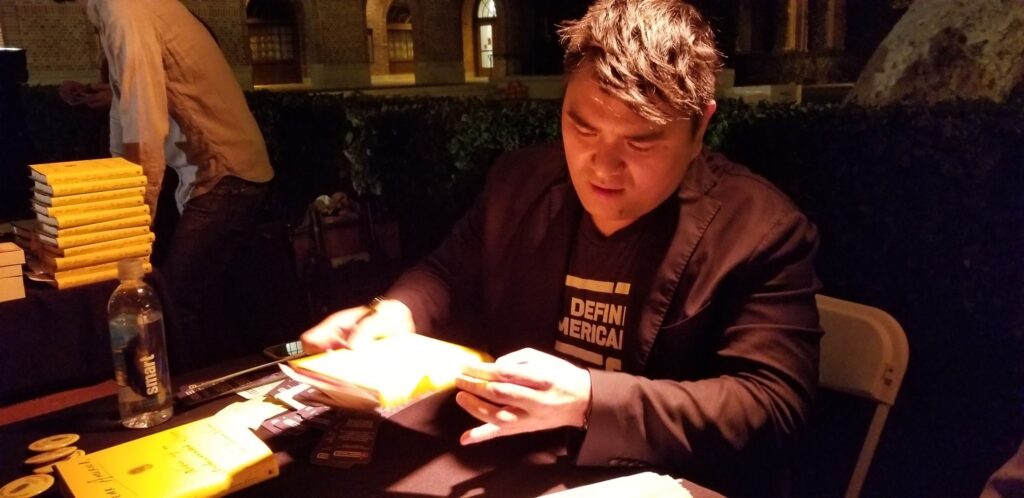

Jose Antonio Vargas in conversation with Prof. Viet Thanh Nguyen, another Pulitzer Prize winning author, at USC Bovard Hall during the book launch of “Dear America” on Sept. 25, 2018 | Photo taken by Prosy Abarquez-Delacruz

My mother wanted to give me a better life, so she sent me thousands of miles away to live with her parents in America — my grandfather (Lolo in Tagalog) and grandmother (Lola). After I arrived in Mountain View, Calif., in the San Francisco Bay Area, I entered sixth grade and quickly grew to love my new home, family and culture. I discovered a passion for language, though it was hard to learn the difference between formal English and American slang. One of my early memories is of a freckled kid in middle school asking me, ‘What’s up?’ I replied, ‘The sky,’ and he and a couple of other kids laughed. I won the eighth-grade spelling bee by memorizing words I couldn’t properly pronounce. (The winning word was ‘indefatigable.’)

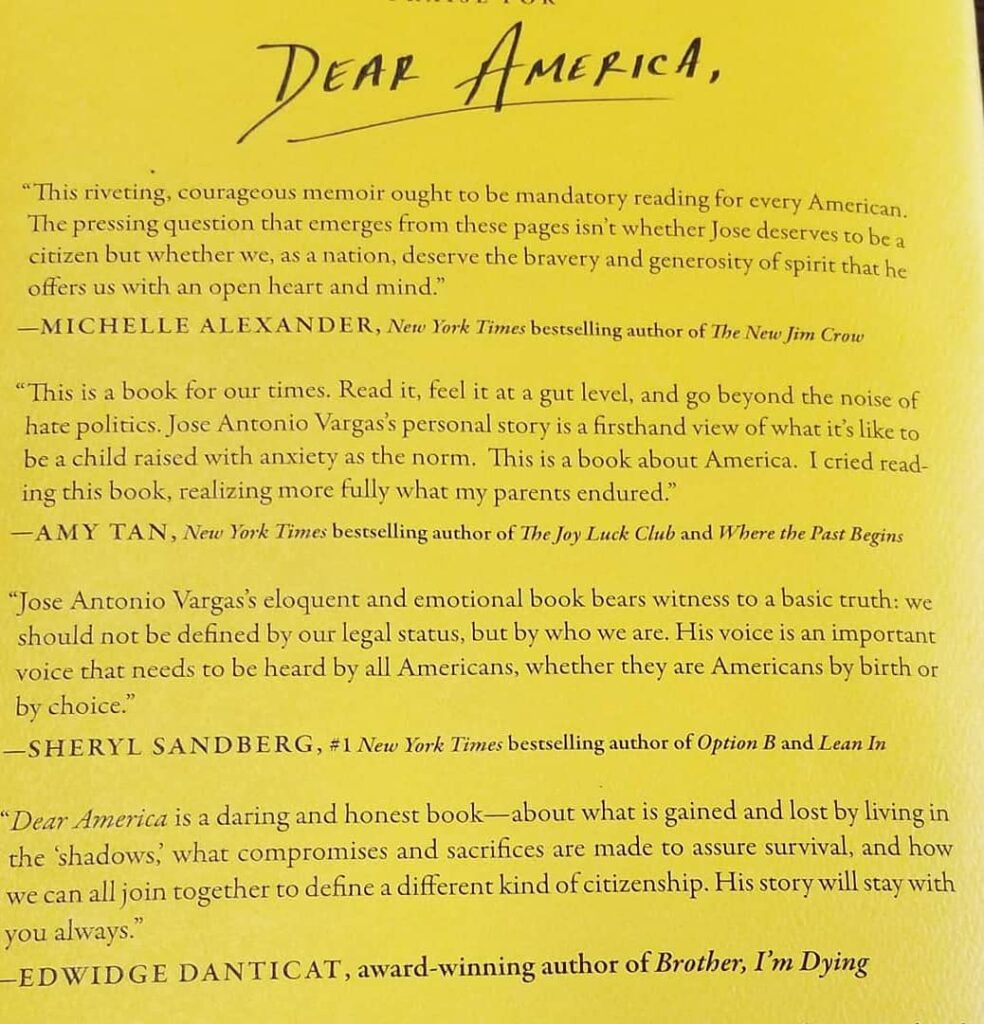

Jose Antonio Vargas, 2011.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about how my heart was broken in reading about toddlers in diapers being tear-gassed, along with their fleeing mothers, at the southern border and how I cried inconsolably, while in meditation.

I felt this inhumanity was un-American and does not reflect what is America, but rather the hatred of White House’s incumbent policies that keeps corroding his “inner vessel,” — his heart. These were families seeking better lives and immigrants seeking asylum based on claims of persecution from homeland gangs or persecution from the failure of their own governments protecting them.

One week ago, I wrote about the struggles of Olivia Quido-Co rising from being an immigrant student in cosmetology, cleaning windows and learning eyebrow threading, to an American citizen-entrepreneur, owning two businesses: a med spa and a storefront for cosmetic products shipped worldwide. She depended on the power of God and the power of tithing, as well as the generosity of her early mentor who helped her with her first business, catapulting her to the current status of looking forward to ‘sky-up’ success.

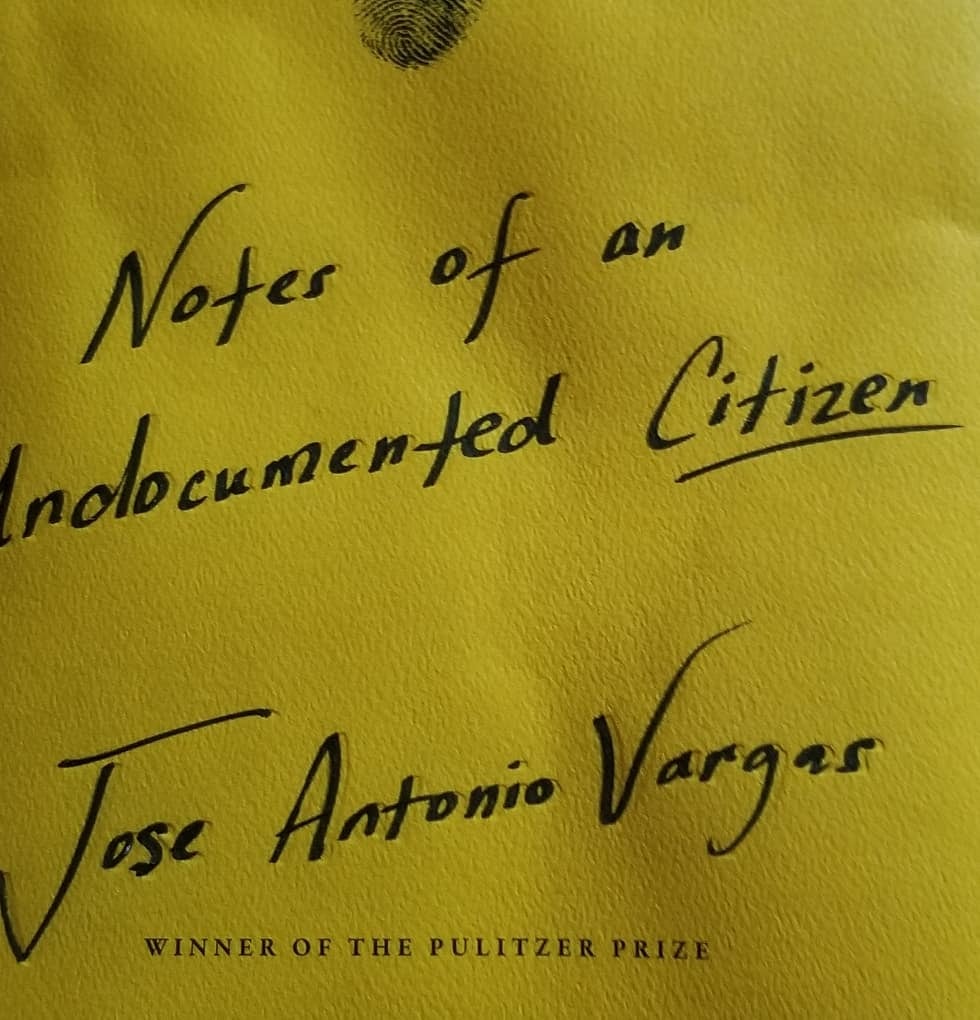

This week, the focus is on Jose Antonio Vargas, an undocumented immigrant, a Pulitzer-prize winning journalist who wrote a Virginia Tech piece that was collaboratively worked on by the Post Team, published in 2007.

Four years later, he wrote a heart-wrenching piece, “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” published in the New York Times Magazine on June 22, 2011. To some of his friends, it was considered legal suicide. But, it was to reconcile the different slices of his selves separated by lies and lies and now the truth, the unvarnished truth of who he is.

He recently had three book launches in Los Angeles in Fall 2018 for his Harper Collins-published-book, “Dear America: Notes of An Undocumented Citizen,” with a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen in September at USC; with Robert K. Ross, M.D. at the California Endowment in October; and with Anthony Ocampo, Ph.D. at the Philippine Expressions Bookshop in November.

How they feel, cut up into pieces

These book launches created a resonance in the community and empathy as to the psychological states immigrants go through — how they feel, cut up into pieces.

First, they must earn a living, like Mr. Vargas. He felt strongly and committed to writing about facts and was careful that his work reflected what was true: “One way I reconciled the lies I told myself was by taking my work very seriously: getting every fact right, insisting on context, telling the truth as much as the truth could be ascertained. I may lie about my status as an undocumented worker, but my work is true.”

Second, they must be careful when they drive lest they are discovered without a valid driver’s license.

In Vargas’ book, he wrote about his encounter with a sheriff in during the 2008 presidential campaign, when he drove 30 miles above the speed limit and was stopped: “As he [the sheriff] walked away from my car to answer the call, I felt something wet trickling down in my pants. I peed myself.”

Luckily for California’s undocumented immigrants, more than a million are now licensed to drive in California, when Assembly Bill 60 became law in 2015. I wonder if Vargas’ coming out as an immigrant without documents had anything to do with it, as for million others?

Third, as lies and lies are told, the inequities become more flagrant as these undocumented immigrants end up paying state and local taxes while residing in the United States, yet reap no benefits, because of their undocumented status.

In “Dear America,” Vargas documents that out of an estimated three million undocumented immigrants in California, more than $3.1 billion are paid by them as state and local taxes.

He cites the nonpartisan Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy, and writes, “undocumented immigrants in the U.S. pay an estimated 8 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes, while the top 1 percent of taxpayers pay an average nationwide effective tax rate of just 5.4 percent. According to the Social Security Administration (SSA itself, unauthorized workers have paid $100 billion into the fund over the past decade. An estimated seven million people are currently working in the U.S. illegally, of whom 3.1 million are using fake or expired Social Security numbers and also paying automatic payroll taxes.”

Yet the false narrative continues that immigrants without documents result in hemorrhaging of the economy as they even take jobs from American citizens. They do not.

What is real, according to Vargas’ research is “undocumented workers pay $12 billion to the Social Security Trust Fund.” It is a trust fund, which the Republicans are eyeing for privatization, or outright conversion as profit centers for investment firms, if at all. It is a trust fund wherein working Americans pay into, documented or undocumented, as an upfront deduction of their take-home salaries.

Vargas makes a powerful argument for intersecting race, class and immigration. He traces the origins of European immigration that were favored and compared them to today’s immigrants who come from Asia and Latin America because of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act.

Vargas cites John F. Kennedy who wrote, in “A Nation of Immigrants, “All told more than 42 million immigrants have come to our shores since the beginning of our history as a nation.” Vargas then learned from his research that “because of a 1965 immigration law that Kennedy and his brothers, Robert and Ted, championed, more than forty-three million immigrants have moved to America since –let that sink in: forty-two million immigrants in 187 years, then forty-three million in fifty years. That’s a lot of change in a perpetually changing America forever resistant to change. It’s no wonder that we are where we are.”

What the book does not cover is how do we move to resolve these internal contradictions in America where racism is much more manifested since the 45th U.S. president was elected? How do we move from resolving trillion dollar federal deficits that this self-interested president approved – an income tax reform that reduces the income tax rate for couples earning $600,000 and above from 39.6 percent to 37 percent and reduces corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, the lowest since 1939, thereby reducing federal income by $1.5 trillion?

It also does not provide an answer to what this African American woman raised when Vargas spoke in Wilmington, North Carolina and wrote: ”I’m not an immigrant. Our people were brought here against our will.”

Vargas describes: “Then she pulled a piece of paper out of her purse and, in a thick southern drawl, continued, ‘Mr. Vargas, my great-great grandmother landed near Charleston, South Carolina, and was given this.’ She opened the yellowed and crumpled paper. It was a bill of sale. I’d never seen one before. ‘Can you connect the paper she got to the papers you and your people can’t seem to get?’

Ponder on that question for a while and allow it to sink into the molecules of your body, into the recesses of your DNA, into your hearts and in your minds.

Human beings are much more than pieces of paper

How is it that a piece of paper has become a permanent symbol of labeling American citizens as less than, and even making them unworthy except as chattel or slave properties up until the era of Jim Crow?

How is it that a piece of paper is presently being denied to eleven million undocumented immigrants because they are labeled falsely as unworthy of becoming American citizens, even if they have led lives more patriotic than others, like serving in the US military to defend American democracy abroad?

Who determines who is worthy or unworthy of being called Americans? The guy in the White House who is now un-indicted co-conspirator of two felonies of paying off two women to hide his affairs and defrauded American citizens as to alter the outcome of the U.S. presidential elections? No wonder the book is entitled Dear America: Notes of An Undocumented Citizen by Jose Antonio Vargas.

America, we have been a nation of absurdities. It is time to make our country more wholesome and correct what is wrong and make everyone who is already here — those who have proven themselves as productive citizens for several years apply to get their legal U.S. work permits and ultimately, after several more years, a permanent green card.

It might take them two decades to qualify until becoming U.S. citizens, but in the meantime, they can operate without being cut up into pieces daily, because of their fears. Just as American chattel owners of slaves terrorize these slaves to remain as properties, today, our American government continues to terrorize these undocumented immigrants and even the asylum seekers at the Southern border fleeing persecution from gangs in their countries.

These undocumented immigrants have been indefatigable, tireless defenders of the American dream and what is right about it; we now have to do what is right by them. America is after all an ideal, an amalgamation of many million immigrants’ dreams who dared cross the shores and oceans seeking better lives, from the Greeks, to the Italians, to the British, to the Irish, to the Spaniards, to the Chinese, to the Japanese, to the Filipinos and over 188 countries now in its borders.

Vargas asserts, “Home is not something I have to earn. Humanity is not some box I should have to check. It occurred to me that I’d been in an intimate, long-term relationship all along. I was in a toxic, abusive, codependent relationship with America, and there was no getting out.”

For these eleven million undocumented immigrants, America has become their cage, a huge jail they cannot seem to get out from, a jail they cannot leave to even visit their loved ones overseas and to some, a jail where they will die from, away from their birth nations.

This December, as we sit at our family table to celebrate Christmas, ponder for a moment the travelling Joseph and Mary, who were denied entry into several homes much like how we cast aside and mistreat the eleven million undocumented immigrants who serve us at restaurants, who care for our young children as nannies, who care for our seniors and our sick elderly as caregivers, who wash our cars in the car wash, who wash dishes in the restaurants, who arrange the flowers in the flower shop, who teach, who are scientists, who write newspaper articles, journal pieces and even books, much like Jose Antonio Vargas!

What are we afraid of, America, when we extend them a pathway to get this piece of paper when we have allowed them into the center of our lives already? It is time for comprehensive immigration reform and to treat these 11 million more reasonably and sensibly.

Published on Asian Journal