Every life is a wonderful story worthy of being told. Every life is a work of art, and if it does not seem so, perhaps it is only necessary to illuminate the reason that contains it. The secret is never to lose faith, to have confidence in God’s plan for us, revealed in the signs with which He shows us the way. If you learn to listen, you will find that each life speaks to us of love. Because love is everything, the engine of the world. Love is the secret energy behind every note I sing and never forget that there’s no such happenstance. There’s an illusion, lawless and arrogant men invented, so that they could sacrifice the truth of our world to the laws of reason.

Andrea Bocelli

While in Los Angeles, Rick Rocamora granted exclusive interview to the Asian Journal, after his book launch of Blood, Sweat, Hope and Quiapo at Echo Park Library in Feb. 2017, sponsored by Sigma Rho Fraternity. We sat down for a few hours recalling all his projects and where he draws his inspiration.

When I read Bocelli’s quotes, Dan Amosin, who wrote a powerful essay in Rocamora’s book about Quiapo and Rodallie Mosende came to mind, a man who rose from poverty, eating one meal a day to now whose assets are worth millions. He was born with seven siblings to parents who were public school teachers.

“I am not bragging, I could not afford then to buy shoes and I would just change the soles,” he said. He rented a bed space in Santa Cruz and bought a kilo or two of liver in Central Market, which he would then cut into little pieces to become his only meal for the day. He was getting the support to go to college from his parents.

After taking a written exam, along with 5,000 applicants, he and 120 students got into the UP College of Law, which tested his equanimity and intelligence. There, he joined Sigma Rho and when his classmates would say, “Let’s eat,” he would then say, “I already did,” as he did not have the money to buy lunch.

One of his fraternity brothers learned of his plight and gave him a job as a consultant to RA 1530, a legislation that was being authored. He transferred to the evening class and worked during the day. He finished his law degree and got employed in a corporate legal department and became the manager of a big corporation. He is now a practicing lawyer in the greater Los Angeles area.

Amosin’s story remains an inspiration to Rocamora’s documentary projects.

Rocamora’s migration to the U.S. after Martial Law was declared was unplanned. Because his wife was an American citizen, he was able to get an immigrant visa quickly. As a successful pharmaceuticals sales representative in the Philippines, he was able to get a job in the same field when he arrived in the U.S. He worked for a New Jersey based company for a year and then was hired by a company that was eventually acquired by Dow Chemical. For 18 years of privileged corporate life in sales and later as the Regional Manager, he remained unhappy because the job did not quite give him the fulfillment in life in spite of the corporate travel perks.

After another company merger, he took a buyout and pursued a career in photojournalism and documentary photography. With passion and purpose, he worked on stories about H1B workers in Silicon Valley, driving while black and brown, and U.S. surveillance of activists through the years for American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). He travelled and made pictures in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Cuba and South Africa which were later published and exhibited. He spent 18 years documenting the lives of Filipino WWII veterans while waiting for equity. In 2009, he published Filipino World War II Soldiers: America’s Second Class Veterans. His photos are also part of a permanent exhibit in San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Perhaps, it is to open our eyes to love human beings as deeply as we can and to aspire for a world that includes them, believing that everyone is entitled to have everything they need in life to thrive and to be healthy. Rocamora’s works capture these universal principles and sometimes, he is fortunate enough to have his eyes become the conduit of human rights and common good.

Common good displaced and called to action

St. John XXIII said, “Of its very nature, civil authority exists, not to confine its people within the boundaries of their nation, but rather to protect, above all else, the common good of the entire family.”

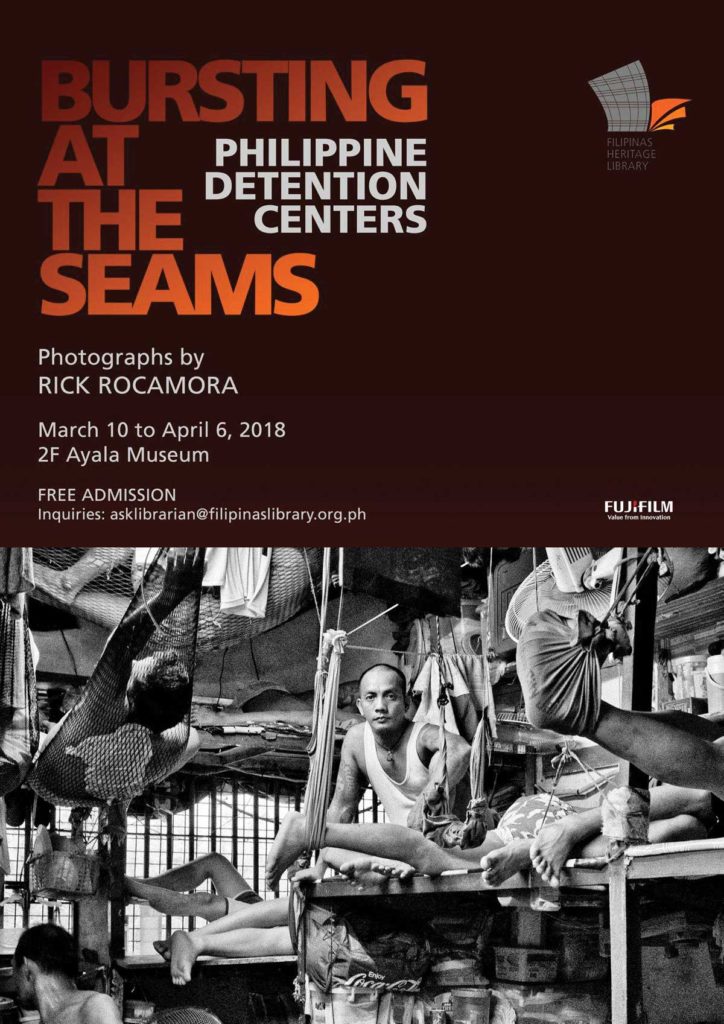

In Rocamora’s personal long term project on conditions of Philippine Detention Centers, he spent six years visiting jails and detentions centers, documenting the plight of Pilipino prisoners and their conditions of “bursting at the seams.”

It was on exhibit at the Ayala Museum from March 10 until April 2018,

with support from the Integrated Bar of the Philippines. “We would like to share with you the good news that the Ayala Museum was awarded Soft Power Destination of the Year – Best Activation by the the Leading Cultural Destination Awards (LCDA) in London for the exhibition Bursting at the Seams! The jury found that it best exemplified the power of a cultural organization to influence and empower their community. The LCDA was organized five years ago by London-based philanthropist Florian Wupperfeld and is considered “the Oscars of museums,” Rocamora posted on his Facebook page.

Esquire Magazine’s Audrey Carpio on March 12, 2018 described this as: “The situation was already bad in 2011, but it has become exponentially worse with the current administration’s war on drugs.”

One image moved me to tears as a father cuddles and hugs his newborn, while his partner sleeps on the floor inside the prison.

“And so what started out as a project for the Supreme Court has evolved into a long-term project that advocates for wide-ranging solutions, which require financial appropriation, structural improvement of facilities and integration of various stakeholders into a single agency. This means that beyond building more and better infrastructure, the jails and penitentiaries all throughout the Philippines—which are currently overseen either by the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, the Bureau of Corrections, and by local government units—all need to be integrated under one body to standardize management protocols. Judges and lawyers, too, have their role to play in ensuring justice is served expeditiously,” Carpio continued.

Another photo of about 24+ men sitting and resting on bunk beds while others in hammocks, occupying every inch of space in that crowded room was compelling. In a Quezon City detention center, Rocamora took a photo of Muslim prisoners praying during Jummah or Friday prayers.

After 9/11, he initiated a project documenting Muslim Americans in various occupations and ways of living, “My goal is to provide Muslim Americans a visual voice through documentary photography. My work will define the community and what they represent in U.S. society and to counteract hate speech, discrimination, profiling and defiling of their sacred spaces. I try to find the stories that says they are one of us.”

“There are 3.3 million Muslims from 77 countries in the world, 30 percent are whites and the rest are from Asia and the Middle East. Without faces, we cannot understand these statistics,” he added.

He recently had an exhibit “Identities of Minority Muslims in the U.S. and Japan” at the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia of The University of Tokyo, Japan from September 29 to October 3, 2018.

From WWII soldiers to collecting cans for a living

After the passage of the Immigration Act of 1990, Rocamora documented The living conditions of the new immigrants after their arrival.Travel agents, luring them to come to the U.S. so they can purchase airline tickets, assured them that they will not encounter housing problems since they are veterans. Many ended up sleeping in homeless shelters on their first night in America. Some were asked to sign a power of attorney so they can be represented for possible monetary claims from the U.S. government.

The story of 10 Filipino veterans brought to the U.S. by Catalino Dazo was published as a series in the San Francisco Examiner. The story highlights their living conditions and their life with Dazo. One of the veterans, Magdaleno Duenas was fed with dog food and tied on a bed post. Others were allegedly used as free labor by Dazo for his other businesses.

With the help of Atty. Lou Tancinco and other Filipino lawyers, and the Contra Costa Sheriff’s office, these veterans were rescued from Dazo. In a civil case, Dazo was found guilty of abuse and was required to compensate the veterans monetarily.

The civil complaint and an investigative story that ran in SF Examiner brought forth a movement and the Veterans Equity Center was founded to assist Filipino Veterans for their needs, including a free legal clinic every Friday given by Lou Tancinco, Esq.

Rocamora’s photos of these blatant human wrongs got seared in our collective memories, as the sufferings of America’s Second Class Veterans. These photos were exhibited at the Canon House Office Building, at the House of Representatives in the Philippines and are now a part of a permanent collection in the SF Museum of Modern Art.

The Rescission Act of 1946 only entitled them to receive 50 cents to a dollar that other veterans were receiving as compensation for their sufferings during the war. New York Times’ Marvin Howe in 1990 described it “Under the law, Filipino veterans were denied all benefits except compensation for service-connected disability or death, paid at a reduced rate.” Yet this 1946 law included the other veterans who fought alongside America in WW II.

The Filipino veterans were finally awarded the Congressional Gold Medal (the highest form of recognition from U.S. Congress) in 2017. In 2009, a one-time equity payment to the surviving veterans was inserted in the special budget allocation, that was championed by Sen. Dan Inouye, and signed by Pres. Barack Obama. It granted $15,000 to U.S. citizens and $9,000 to non-citizens, based on proof of verifiable military service.

At the time of Rocamora’s book launch in 2009, only three of the book’s subjects were still alive and it was his wish to “give them a tribute, to their contributions to this country [America], and also to remember the injustice they suffered while waiting for equity.”

Nurturing an irrepressible artistic spirit

Rocamora was commissioned by UNHCR to take photos during Typhoon Haiyan, a cyclone that devastated not his home province, yes not his home province, yet he was thrusted in harm’s way in Leyte.

He captured the destruction of howling 145 mph winds resulting in 6,300 deaths in 2013. Without power and transportation, he spent a month travelling on foot, and when available, used tricycles and took photos to document hope, teamwork, sacrifices, even while he was surrounded by a tsunami of dead bodies, mangled limbs, floating bodies, apocalyptic uprooting of homes from their foundations, flying roofing sheets pried open like sardine can tops.

With his irrepressible artistic spirit, he was able to capture hope in his photos. Like a boy who was holding a basketball or a flag that flew amidst the rubble or even signs of rosaries or a cross, surrounded by destruction. It is the hopeful eyes of Rocamora that allow us to see beyond the tragedy to hope for a new tomorrow.

How did you survive, I asked? “Skyflakes and water,” he said, without

a tinge of self-pity. “I slept on a piece of cardboard inside a building. There, I met a South African family living in Indonesia who came to help in Cebu and found their way to Leyte. They gave me a bag of beef jerky.”

He was once described as the person who would not hold anything back

in pursuit of his artistic endeavors or to invite generosity to his chosen subjects. For example, Rodalie Mosende, a homeless girl, who with grit and determination transcended her life of living, studying, and doing homework in the streets of Quiapo to what she has become now, with a college degree, working, not living in the streets anymore and with her own family to raise. When Mosende graduated, a fellow Lyceum graduate, Pres. Rodrigo Duterte was the commencement speaker.

Your work seems to be well-exhibited, I said, and to which he responded, “If you have good work, it will find its way to exhibition walls. I seek it from time to time, as I am always thinking of the subjects, it is about reaching a target audience, it is always about them, not me. The documentary exhibit is providing a visual voice to your subjects.”

In his travels, he learned to speak Zulu, Chinese, Spanish, Vietnamese and Korean, saying “Thank you and I am fat,” in all these languages.

As a young boy in Nueva Ecija, he cultivated deep interest in politics by attending political rallies. In high school, he read the daily newspapers in the barber shop near his home to be on top of current events. He studied political science in UP Diliman.

His guiding principles on photography embody the common good. “To be

able to give a visual voice to your subjects, you have to feel their pain, anger and anxiety in order to make images that reflects who they are. It is not about us but always about them,” he said.

His photos dignify thousands of lives and uplift them to be in parity with the viewer and to be considered as part of humanity.

Published on Asian Journal