“Yes, Martial Law is now over. The cruel tyrant had died. But there were other perpetrators during this gruesome era, and many of them are still around today. Now, they use their ill-gotten wealth to attempt to rewrite history and boldly proclaim to the present generation, who were not even born during the dictatorship years, that Martial Law is good for our country. We, who were arrested, tortured, and left to rot in prison, continue to “rebel” against these people who dare to rewrite and revise our history of struggle against the evil tyranny of “One-Man Rule.” Let the “Wall of Remembrance” be our altar where the names of our martyrs and heroes are forever enshrined as a reminder that we who have survived this cruel and dark portion of our history will rise up once again and tell (write) our stories: 1. Stories of defiance and struggle in the face of tyranny, 2. Stories of determination and courage under torture and physical degradation, 3. Stories of indigenous peoples rising up to defend their ancestral lands with their lives and 4. Stories of martyrdom and the sacrifice of one’s life so that others might live. Nunca Mas! These are the stories that uplift the human spirit, because we believe that our brothers and sisters did not die in vain.” – Manuel C. Lahoz, “Of Tyrants and Martyrs: A Political Memoir” Published by The University of the Philippines Press, Diliman, Quezon City, 2017.

I have read several books on “One-Man Rule”: Raissa Robles’ Marcos Martial Law: Never Again; Susan F. Quimpo and Nathan Gilbert Quimpo’s Subversive Lives; Primitivo Mijares’ Conjugal Dictatorship, Monina Allaret Mercado’s People Power: The Philippine Revolution of 1986 and Ninotchka Rosca’s A State of War, a captivating novel which I could not put down for three consecutive nights.

I am reading Manuel C. Lahoz’s Of Tyrants and Martyrs and still rereading chapters, as I believe it is one of the best books on the “One-Man Rule” of Ferdinand Marcos. It explains in layers how life decisions were made, how one gets arbitrarily arrested, even without any apparent crimes or wrongs done.

It presents an insider’s view of what happened to the high school principal, to the deacon, to the band leader, to the nun, to the priest saying the mass then assassinated, to the oppressed farmers and workers, to the indigenous tribes people who defended their tribal lands from being denuded and defiled by the construction of the Chico Dam.

Manny Lahoz’s book is to be relished and savored, as if God is near you, as Manny’s loving and literary soul is etched in every page of this political memoir. He has eyes that observe every minute detail of each person he met.

As a reflective person, he is acutely aware and conscious of what his life’s purpose is: “gradually, as in a self-revelation, it dawned on me that there was more to being a priest than just a minister of the sacraments. I had taken the first steps towards the ministry of sevice, which was more than just offering the sacraments to the people, when I made a commitment to be with and be part of the poor and the oppressed in their struggle for justice. I would follow this ministry of service for many years to come.”

One of the best books on “One Man Rule”

Nestor Castro, Vice Chancellor for Community Affairs in UP Diliman affirms the writings of Lahoz, the author, and also attested to how, he too was imprisoned at Camp Dangwa, Benguet in 1983 and chose to block the details from his memory.

I also found convergence in my assessment, after reading Francisco Lara, Ph.D.’s “Le Politique Du Ventre” mirroring my notes, yet more his eloquent words are much more beautiful: “each chapter has a section where simple tasks and the local knowledge of the poor is shared to the reader—such as, how do you repair a section of a destroyed rice terrace (with brains rather than brawn); or cook molasses to sweeten a rice cake (with the right heat and the best rice); or take a dump [referred to in the US as #2] in the forest, with native pigs surrounding you (with sticks and stones), or walk through a hanging bridge without trembling in fear (by looking ahead and not below).” This is where Lahoz’s sense of humor is vividly in display, particularly in how to take a dump.

The book is a first witness account of what happened to the martyrs and even verified by newspaper accounts, Bantayog ng mga Bayani’s account, and other authors. It satisfies the known standard of “believe the assertion, but also verify,” and in one instance, the author even provides three different accounts of what happened to Santiago Arce: laying out the PC Commander’s version of Mr. Arce’s death, the Judge’s Inquest, and the People’s Reaction to the PC Commander’s Version of Arce’s escape.

The reader equipped with critical thinking skills can discern the details around the Arce’s escape, advanced by the PC Commander, as his use of a gun as improbable and the judge’s inquest more credible and believable – given a simple examination of the gun barrel that was shiny and without bullet residues, confirming Mr. Arce did not use a gun, as falsely asserted by the military.

It also contains details of Arce’s longest funeral in Abra with twenty priests concelebrating the mass and a funeral procession of about a kilometer long, four abreast, making a long procession of Abrenians walkng 0.62 miles.

Why did Arce merit a hero’s funeral?

Santiago Arce was Little Flower High School’s principal, who was also an ordained church deacon, a band leader who led the best marching band in Abra, and helped provide seminars to the farmers.

He describes in vivid details what it is like to have fish caught from the streams and banana blossoms gathered from the forests and then to enjoy eating the charred grilled fish with steaming aromatic rice cooked in bamboo tubes, with cooked banana blossom; half-cooked rice wrapped in woven palm leaves dunked into boiling syrup. He even details the livelihood of folks, and how sugar cane is grown in sandy loam soil, then, harvested and milled into cane juice then molasses, and how lumber is gathered from cut trees, and how at the peak of deforestation – about 50,000 logs await in the river, to be milled and turned into paper. He even describes how a carabao is slaughtered.

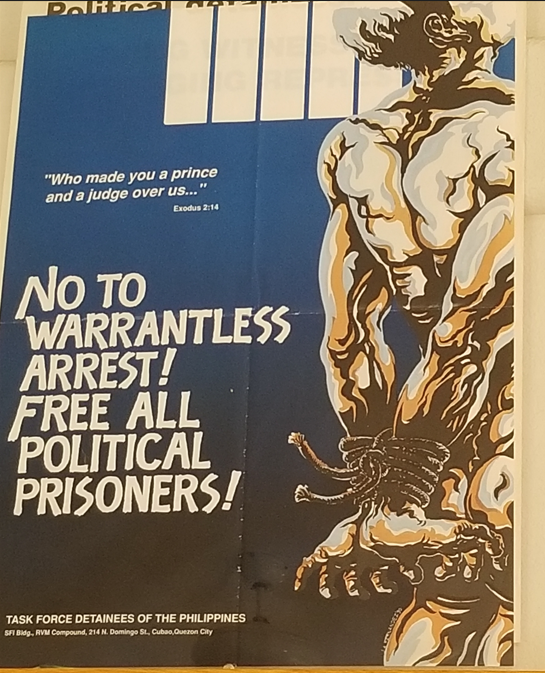

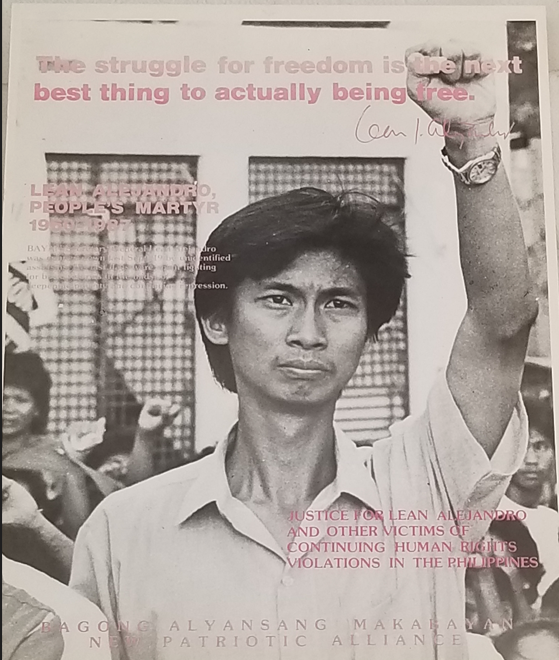

The book ‘s details allow us a glimpse into that period where fear predominates first, until conviction makes one stand up and others as well, “the members of the FFF (Federation of Free Farmers) attended the funeral procession in big numbers, unafraid of the presence of the military spies.” It makes us recall the longest procession accorded Lean Alejandro who was reportedly assassinated by Marcos’ military and over 50,000 people lined up the streets to show their sympathy but also their protest to the “One Man Rule.”

Lahoz wrote about the assassination of Ama Macli-ing Dulag, who spoke of the land being one with their tribes, “If the land could speak, it would speak for us. It would say like us, the years have forged the bond of life that ties us together. It was our labor that made the land she is. It was her yielding that gave us life. We and the land are one!”

“Dulag was murdered for speaking out,” Lahoz wrote, “Dulag’s death was planned from the very beginning when he championed the rights of Kalinga and Bontoc peoples against the Chico Dam, a pet project of Marcos with $160 million funding from the World Bank. The proposed Chico Dam was envisioned to provide nearly 2,000 megawatts of hydroelectric power. It would irrigate 65,000 hectares and keep industries and manufacturing companies in Manila running. On the other hand, it would submerge three towns in Mountain Province and five in Kalinga. Nearly 100,000 hectares of ancestral lands, rice fields, farms, forests, hunting grounds, water sources, natural orchards, burial grounds, and pastoral lands would be submerged and lost forever. Some 250,000 Bontocs and Kalingas would be directly relocated,” Lahoz wrote, and he meticulously footnoted who orally shared and related the stories to him, including itemizing the list of 11 donors, priests and nuns, who contributed Php 7,000 each for the Grand Bodong in the Cordilleras.

He wrote about the cultural workers and “the Kalinga women proceeded to approach the bulldozer from the north, the Igorot warriors with their gongs beaten in crescendo, defiantly encircled the engineers like hunters entrapping their prey. With engine roaring, the bulldozer operator continued to do his work approaching the Igorot women coming from the south side. With barely about fifteen meters away, the moving giant machine and the dancing Igorot women were on collision course. The spectators started to cry in alarm. Suddenly, the Igorot women stopped, went down on their knees, ripped their blouses open and bared their breasts, with heads tilted upward to the heavens and arms outstretched as if trying to grab a piece of the sky.“

“They cried as one in a loud voice, “Dagami daytoy, pumanawkayo!” (This is our land, leave us alone.) The operator stepped on the brakes and stopped the giant earth-moving machine with barely five meters to spare. Read more on this chapter as “President Marcos decided to unleash the military powers to confront and crush the united opposition of the Bontocs and Kalingas led by their brave and charismatic leader Ama Macli-ing Dulag. The massive use of military in suppressing the population did not go unnoticed by the leaders of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).”

“It was a silent retreat, but it did not detract from the fact that the Bontocs and Kalingas had accomplished something rare in a third world country, the [World] bank’s withdrawal in the face of popular resistance, “ economist Walden Bello had said.

With such robust capacity of observation and memory recall, the blood pouring out of the carabao’s jugular vein in his neck, makes for a visual sensory metaphor for how the women and men were arrested, tortured in prison and how women were raped wantonly by a gang of military men, leaving red blood taints all over the place.

Lahoz describes these incidents of torture with precision and specificity, yet with such respect for the women and the reader as to spare us the gory details of the criminal acts, and leaving us to imagine the atrocity, while describing the details after the gory incident. We came to know the various methods of torture, including the use of flat iron to sear the soles of the prisoners, the grabbing of hair until they are torn off one’s scalp with brute force.

Many good deeds are equally described, including soldiers who give a hand to the tortured prisoners, or how Abra farmers were supported by construction of irrigation systems funded by the Catholic Lenten Fund of Germany, enabling the farmers to have two croppings a year.

You could sense the tedious verification that the book went through, as he writes about ordinary people in these chapters and then, through a series of circumstances and the decisions they made, we sense how noble they are, through the words that Manny used in writing this book, not flamboyant, but precise enough for a person to appreciate how a pregnant woman is helped by movement allies to give birth to her child and even a lesson on how to make spaghetti by her host only to cook this spaghetti using sardines with canned tomato sauce, and a separate red sauce for Manny.

It was a gift from her heart to Manny, appreciating how she and her child were sheltered from harm. What is the big deal, as the book asks? Spaghetti is not something you can simply buy at the country store in that period; imagine eating this at a remote village where one has to walk by foot for miles to reach the highway. So, one is left wondering? How did she make the spaghetti? The woman thought of keeping the spaghetti noodles she got from her host family and kept it with her for months, on the mere chance she would see Manny and thank him for what he did for her.

Who was Manny Lahoz’ muse?

Even before coming to the US, he had already written half of this book. But when he got to Chicago, he encountered writer’s bloc. It was an imagined conversation with Padre Zacarias Agatep (who was assassinated) that got the words to flow again. The outpourings of events were so fast for his slow hands to capture, that at some point, his handwriting was labored.

Who was Fr. Agatep? He entered the Immaculate Conception Minor Seminary in Vigan and ordained a priest in 1965, assigned to a small parish of Banayoyo, Ilocos Sur. When he heard a presentation of the Federation of Free Farmers (FFF), “he asked the permission of his bishop to become a full time chaplain and organizer for FFF,” Lahoz wrote, “Like Paul of Tarsus, who found Christ on the road to Damascus, Zacarias followed Dean Montemayor on the road to Mamatid, Laguna, to study the gospel according to Montemayor.”

Imagine fulfilling your dream to be an author at 76 yo? He wrote this first book, dedicating it “to Mia, Karl and Angela…that you may learn what really happened during the martial law years.”

In the United States, he held book launches in Minnesota, Chicago, New York, Oakland, West Covina and Carson. In one book launch, a disabled young student in a wheelchair remarked, “Can you give us some hope? I am hearing mostly borrowed understanding from my parents.” It piqued with such intensity that I responded – You are looking for hope – the fact that he survived the trauma and not allow the trauma to sink him into depression is hope. The fact that he is doing book launches at age 76 and caring enough that the true accounts of these martyrs are shared is hope. Also, you can have your primary understanding, not relying on your parents’ borrowed understanding by reading the book fully, by interviewing known martial law survivors and discern for yourself why there is hope in standing up for what is right, why there is hope in standing up for the truth, why there is hope in relying on true accounts, and not the opinionated false claims that it is fake news.

`